A Brief Note on Quotient Maps

And how they relate to quasi-homeomorphisms

(PDF version of this post.)

In the previous post I introduced quasi-homeomorphisms; these are related to another important topological concept, quotient maps. Quasi-homeomorphisms are in fact just a special kind of quotient map, one that discriminates as finely as is possible for any continuous function on a given domain.

Definition. A quotient map is a surjective (onto) function 𝑞 : 𝑆 → 𝑇 between topological spaces such that any set 𝑉 ⊆ 𝑇 is open if and only if 𝑞⁻¹[𝑉] ⊆ 𝑆 is open.

This definition ensures that the topology on 𝑇 is precisely the one “induced” by 𝑞 from 𝑆, with no extra or missing open sets. This definition implies that quotient maps are continuous: a subset 𝑉 of 𝑇 is open only if 𝑞⁻¹[𝑉] is open in 𝑆. Since a quotient map 𝑞 must be continuous, it is required that 𝑞(𝑥) = 𝑞(𝑦) whenever 𝑥 ∼ 𝑦 (𝑥 and 𝑦 are topologically indistinguishable).

Quotient maps and equivalence relations

Quotient maps are related to equivalence relations. Recall that an equivalence relation ≈ is a sort of poor-man’s equality, one that throws away some of the information in its arguments but otherwise behaves like equality in that it is reflexive (𝑥 ≈ 𝑥), commutative (𝑥 ≈ 𝑦 iff 𝑦 ≈ 𝑥), and transitive (𝑥 ≈ 𝑦 and 𝑦 ≈ 𝑧 implies 𝑥 ≈ 𝑧). Examples we’ve seen include equality ( = ), logical equivalence of propositional formulas ( ≡ ), and topological indistinguishability ( ∼ ).

The set of values equivalent to 𝑥 is the equivalence class of 𝑥, written

or just [𝑥].1 The entire collection of equivalence classes for an equivalence relation ≈ on a set 𝑆 is known as the quotient space that ≈ induces on 𝑆, written 𝑆/≈. (It’s called the quotient space because it divides up—partitions—the space 𝑆 into equivalence class.) The quotient topology on the quotient space defines a set 𝑈 of equivalence classes to be open iff their union is an open set in 𝑆.

For a given equivalence relation ≈ on 𝑆, if we define 𝜋 : 𝑆 → (𝑆/≈) such that 𝜋(𝑥) = [𝑥], then 𝜋 is a quotient map:

𝜋 is surjective: every 𝐸 ∈ (𝑆/≈) is an equivalence class, and every equivalence class 𝐸 has at least one member 𝑥 ∈ 𝑆, so 𝐸 = 𝜋(𝑥).

𝑉 ⊆ (𝑆/≈) is open iff the union of its elements is open in 𝑆. But the union of the elements of 𝑉 is the set of all 𝑥 ∈ 𝑆 whose equivalence class is in 𝑉; that is, the set of all 𝑥 ∈ 𝑆 such that 𝜋(𝑥) ∈ 𝑉, and this is just the definition of 𝜋⁻¹[𝑉]. So 𝑉 is open iff 𝜋⁻¹[𝑉] is open.

Conversely, any quotient map 𝑞 : 𝑆 → 𝑇 induces an equivalence relation on 𝑆: define 𝑥 ≈ 𝑦 iff 𝑓(𝑥) = 𝑓(𝑦). Then 𝑇 is homeomorphic to (𝑆/≈), that is, there is a bijection 𝑓 : (𝑆/≈) → 𝑇 that pairs up corresponding elements of (𝑆/≈) and 𝑇, such that both 𝑓 and its inverse 𝑓⁻¹ are continuous.

For a geometric example of a quotient map, consider the set 𝕊¹ ⊆ ℝ², defined to be the unit circle:

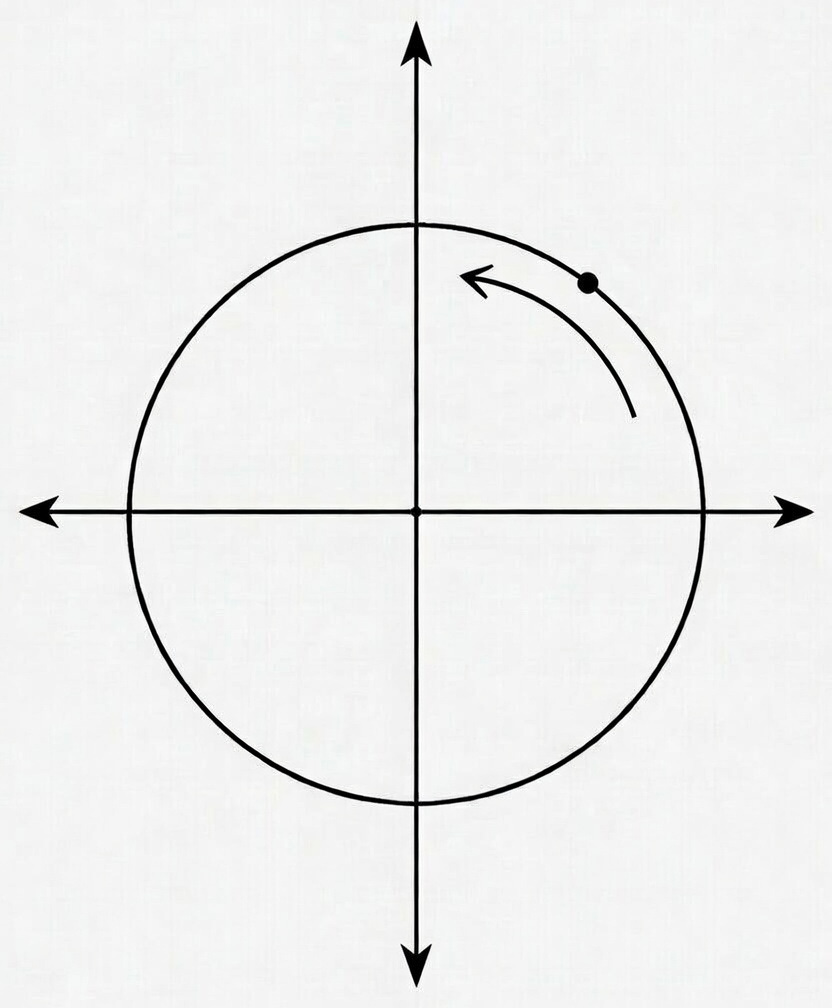

Then the function 𝑓 : ℝ → 𝕊¹ defined by

is a quotient map, assuming the standard topologies on ℝ and ℝ², and assuming for 𝕊¹ the subset topology induced by ℝ². If we think of 𝑡 as time, and 𝑓(𝑡) as the position of a dot on the plane at time 𝑡, then the dot moves counterclockwise in a circle at a constant speed of one unit of distance per unit of time (see figure below). Since 𝑓(𝑠) = 𝑓(𝑡) iff 𝑠 and 𝑡 differ by a multiple of 2𝜋, the equivalence relation associated with 𝑓 is then 𝑠 ≈ 𝑡 iff 𝑠 ≡ 𝑡 (mod 2𝜋).

Note that if we had written 𝑓 : ℝ → ℝ² then 𝑓 would not be a quotient map, because it would not be surjective. The codomain 𝑇 (set of potential values) of a function 𝑔 : 𝑆 → 𝑇 must be considered part of its identity, not just its range (set of actual values attained).

Although we have defined a quotient map 𝑞 : 𝑆 → 𝑇 in terms of the topology on 𝑇, one often goes in the other direction: start with a surjective function 𝑞 and then define the topology on 𝑇 to be the one that makes 𝑞 a quotient map:

That is exactly how the quotient topology on a quotient space was defined, starting with the function 𝜋.

Quotient maps and quasi-homeomorphisms

Recall the definition we gave for a quasi-homeomorphism: a function 𝑓 : 𝑆 → 𝑇 between topological spaces having the following properties:

𝑓 is surjective (onto).

𝑓(𝑥) = 𝑓(𝑦) iff 𝑥 ∼ 𝑦 (𝑥 and 𝑦 are topologically indistinguishable).

𝑓 preserves open sets both ways:

If 𝑈 ⊆ 𝑆 is open then 𝑓[𝑈] ⊆ 𝑇 is open.

If 𝑉 ⊆ 𝑇 is open then 𝑓⁻¹[𝑉] ⊆ 𝑆 is open.

Property 2 can be simplified to “𝑓(𝑥) = 𝑓(𝑦) only if 𝑥 ∼ 𝑦,” as the “if” direction is implied by Property 3b (continuity). But once we have the concept of a quotient map, we can further simplify the definition:

Proposition. A quasi-homeomorphism 𝑓 is a quotient map such that 𝑓(𝑥) = 𝑓(𝑦) only when 𝑥 ∼ 𝑦.

Proof. ( ⇒ ) Suppose 𝑓 is a quasi-homeomorphism. Then it is surjective (Property 1). If 𝑉 ⊆ 𝑇 is open then 𝑓⁻¹[𝑉] ⊆ 𝑆 is open (Property 3b). If 𝑓⁻¹[𝑉] is open then, by Property 3a, 𝑓[𝑓⁻¹[𝑉]] = 𝑉 is open. So 𝑓 is a quotient map. And, of course, Property 2 guarantees that 𝑓(𝑥) = 𝑓(𝑦) only when 𝑥 ∼ 𝑦.

(⇐) Suppose that 𝑓 is a quotient map such that 𝑓(𝑥) = 𝑓(𝑦) only if 𝑥 ∼ 𝑦. Since 𝑓 is surjective, Property 1 is satisfied. Since 𝑓 is continuous, Property 3b holds; furthermore, continuity implies that 𝑓(𝑥) = 𝑓(𝑦) if 𝑥 ∼ 𝑦, and so both the “if” and “only if” directions of Property 2 hold.

It remains only to show that Property 3a holds. Suppose that 𝑈 ⊆ 𝑆 is open. Since 𝑓 is a quotient map, 𝑓[𝑈] is open iff 𝑓⁻¹[𝑓[𝑈]] is open. If we can show that 𝑈 = 𝑓⁻¹[𝑓[𝑈]], then Property 3a does indeed hold. But 𝑈 ≠ 𝑓⁻¹[𝑓[𝑈]] only if there is some 𝑥 ∈ 𝑈 and 𝑦 ∉ 𝑈 with 𝑓(𝑥) = 𝑓(𝑦). But 𝑓(𝑥) = 𝑓(𝑦) implies that 𝑥 and 𝑦 are topologically indistinguishable, and 𝑈 is open, so they either both belong to 𝑈 or neither belongs to 𝑈. ∎

The codomain of a quasi-homeomorphism is 𝑇₀

In the previous article I claimed that if 𝑓 : 𝑆 → 𝑇 is a quasi-homeomorphism, then 𝑇 must be a 𝑇₀ space: all distinct points of 𝑇 are topologically distinguishable. I did not give a proof, thinking it was a simple one-liner, but upon looking more closely I realized that the proof is more involved than that. Therefore I’ll give the proof now.

Theorem. If 𝑓 : 𝑆 → 𝑇 is a quasi-homeomorphism then 𝑇 is a 𝑇₀ space.

Proof. Suppose that 𝑡₁, 𝑡₂ ∈ 𝑇 and 𝑡₁ ≠ 𝑡₂. We will show that 𝑡₁ and 𝑡₂ are topologically distinct.

Since 𝑓 is surjective there exist 𝑠₁, 𝑠₂ ∈ 𝑆 with 𝑓(𝑠₁) = 𝑡₁ and 𝑓(𝑠₂) = 𝑡₂. As 𝑡₁ ≠ 𝑡₂ it follows that 𝑓(𝑠₁) ≠ 𝑓(𝑠₂), so by Property 2 the points 𝑠₁ and 𝑠₂ are topologically distinguishable. Therefore there is an open set containing one but not the other; without loss of generality, assume that there is an open set 𝑈 ⊆ 𝑆 with 𝑠₁ ∈ 𝑈 and 𝑠₂ ∉ 𝑈. By Property 3a, 𝑓[𝑈] is an open set in 𝑇, and clearly 𝑡₁ = 𝑓₁(𝑠₁) ∈ 𝑓[𝑈].

For any 𝑠′ ∈ 𝑆, if 𝑓(𝑠′) = 𝑡₂ then 𝑓(𝑠′) = 𝑓(𝑠₂), hence 𝑠′ ∼ 𝑠₂, hence 𝑠′ ∉ 𝑈. Therefore 𝑡₂ ∉ 𝑓[𝑈], and we see that 𝑓[𝑈] is an open set containing 𝑡₁ but not 𝑡₂, hence 𝑡₁ and 𝑡₂ are topologically distinguishable. ∎

One last note

One thing I may not have made clear enough is the relation between homeomorphisms and quasi-homeomorphisms. If every pair of points in space 𝑆 is topologically distinguishable—𝑆 is a 𝑇₀ space—then a quasi-homeomorphism from 𝑆 to 𝑇 is exactly the same thing as a homeomorphism from 𝑆 to 𝑇. And if 𝑆 does contain any pair of points that are topologically indistinguishable, then it is impossible to have a homeomorphism from 𝑆 to 𝑇, because any continuous function 𝑓 : 𝑆 → 𝑇 must map topologically indistinguishable points in 𝑆 to the same point in 𝑇, and hence can not be one-to-one in this case.

In summary, for any topological space 𝑆, either

𝑆 is a 𝑇₀ space, so homeomorphisms 𝑆 → 𝑇 and quasi-homeomorphisms 𝑆 → 𝑇 are the same thing; or

𝑆 is not a 𝑇₀ space, so there exists no homeomorphism 𝑆 → 𝑇.

Yes, that conflicts with our notation for the set of satisfying truth assignments for a propositional formula—although [𝜑] (the equivalence class) and [𝜑] (the set of satisfying truth assignments) are closely related.)

Brilliant framing of quasi-homeomorphisms through the quotient map lens. The way this reframes Property 3a by showing U = f⁻¹[f[U]] when dealing with topologically indistingusihable points really clicked for me. I once got stuck tryingto prove something similiar in a measure theory context, and seeing the connection to equivalence relations would've saved me hours. The unit cirlce example nails why we care about codomain versus range too.